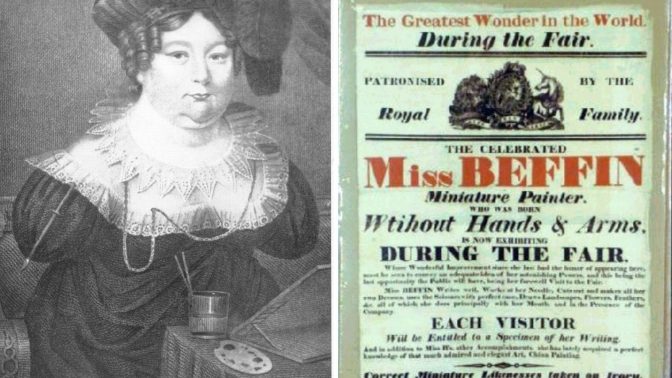

It is the late 18th century and a family has gone to visit a kind of show that today has died out. Indeed it would quite rightly be frowned upon today as exploitative and wrong. But in the 18th and 19th centuries the tradition of the freak show was alive and well and this particular show involved a teenage girl from the Quantocks with an extraordinary talent: the esteemed painter Sarah Biffen.

A rural teenage girl at this time being an accomplished painter in itself is unusual enough (unless she was rich and had had regular lessons as a child), but that is not what is drawing attention to Sarah Biffen. Sarah Biffen is in the freak show because she was born with no arms and only vestigial legs. She cannot paint in the normal way, so she paints, to an extraordinary standard, with the brush held in her mouth!

Sarah was born in East Quantoxhead in 1784. She was the daughter of a farming family. Although East Quantoxhead, with its connections to the Luttrell family, might have been more connected than some places with the wider world, East Quantoxhead was still an extremely rural place. At the time that Sarah was born there would have been extensive discrimination towards disabled people, and the idea of her leading a normal life would have been unlikely. The most likely outcome for her would, if her family wanted her, for her to live at home her whole life with very few opportunities. But she was encouraged in her education and learned to read and to write using her mouth and at the age of 13 Sarah’s life changed. There was a downside to this, she would be exploited and underpaid, but she also had an extraordinary career that would have been hard to imagine as a farmer’s daughter.

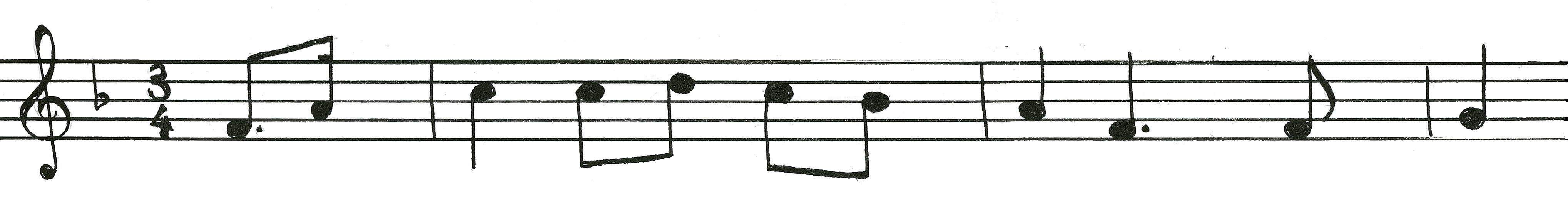

The dramatic change in her life came about when she was apprenticed to a man named Emmanuel Dukes. Dukes saw her talent and began to take her around the freak and sideshow circuit. Although she had begun to paint and created landscapes and miniatures portraits on ivory, rather than her work being exhibited, it was rather Sarah who was the exhibit. People came, not to see her art, but rather to see the spectacle of a disabled girl painting, drawing and even sewing using her mouth. One can only imagine how strange this must have felt for Sarah. She wasn’t even paid properly with some saying Dukes paid her as little as £5 a year – considerably less than she would have made for him.

However Sarah’s life changed again in 1808 when her talent was spotted by George Douglas, the Earl of Morton, who when he was convinced of her ability, paid for her to have proper art lessons with the Royal Academician William Craig. Her career advanced once she left the freak shows and in 1821 her talent was properly recognised when she received a medal from the Society of Arts and her work was accepted into the Royal Academy, the gold seal of approval for any professional artist at the time. She became incredibly popular as a portrait painter and even painted portraits of the royal family! This led to her setting up her own studio on Bond Street in London.

Yet Sarah’s reliance on others, including the men who sponsored her career, continued to affect her success and livelihood. In 1827 George Douglas died and Sarah began to struggle financially. Eventually she was awarded a civil list pension by Queen Victoria. She married a Mr Wright and retired to Liverpool, never quite regaining her painting success again. She died at the age of 66 in 1850.

At this point Sarah Biffen’s career falls into obscurity. Such an extraordinary life and talent, a life that took her far away from her Quantock farming roots, through freak shows, high society to a quiet retired married life in the north of England. Yet in recent years Sarah has begun to be recognised again. At a time when people are quite rightly looking to uncover forgotten stories of diversity in history, at a time where visibility for the disabled community and recognition of talents is increasingly important, Sarah is being remembered for her achievements. Her work has soared in value – one small portrait recently selling in 2019 for £137,500 at Sothebys. It is a vast sum of money, and bittersweet when such a talented artist died in relative obscurity and poverty. But nevertheless it is a rightful recognition for this Quantock woman, who painted extraordinary delicate detail, beyond what any of us could ever hope to do with our hands, with a paintbrush held in her mouth.