In 1871 the English Illustrated Magazine published an essay called “Summer in Somerset.” It was by the eminent nature writer Richard Jefferies and depicts his wanderings through West Somerset, including the Quantocks, with beautiful detail. It conjures up not just the wildlife and plants abundant at the time, but also the atmosphere, the feeling of the area at this moment in time, in a way that more factual historical records do not.

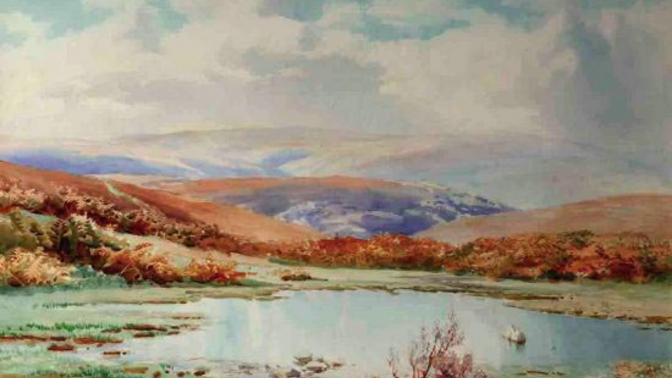

The piece starts by water in a steep coombe – the Barle as he refers to it and a deep green pool. Much travel and nature writing would start with a naming of place, but Jefferies rather than name, seeks to conjure it, immersing his reader in colour and detail. We could be anywhere yet only in this one place, with its flora and fauna, unique in that moment in a 19th century Somerset June. Whortleberries smear the ground, leaves, flowers, water. There is a sense that this landscape is alive, that the deep green pool he describes in such detail is a sentient creature, that each place deserves the detail we would give the personality of a human character in a story.

We are a few pages in before Jefferies mentions a place name Torre (presumably Tarr) Steps, then Dulverton. We are in the Exe valley and his description up to this point makes sense in this context. But till this moment we could have also been in a steep Quantock coombe – his writing travels and place behaves in strange ways. It is location as feeling – Somerset as feeling. We are in the Exe valley, then before we know it he is gazing upon the heights of Wills Neck and we are in the Quantocks.

Obviously this is some distance and far too far to walk in one go, but the immersive nature of his writing makes you feel as if floating through from place to place, held by the atmosphere, held by the true essence of the landscape. As Jefferies says: “From the Devon border I drifted, like a leaf detached from a tree, across to a deep coombe in the Quantock hills.” It is as if he senses a strange connected between these two steep wooded valley landscapes, a Somerset kinship, a spirit of place.

Jefferies’ writing then becomes more anecdotal in nature. He mentions highwaymen and drovers. Old farming methods such as threshing corn with flails, the hard nature of this work (see pixies – no wonder there is a folktale of getting help with this!), how also in Somerset people still use sickles, how they sharpen them by running them through apples, the acid cleaning the steel.

Jefferies also mentions folk traditions he comes across, such as Oak Apple Day celebrations. This is the 29th May so if he visited in June the remnants of festivities would still be around. Jefferies witnessed how people used to celebrate, noticing the oak branches at people’s doors and how to his knowledge this was in memory of King Charles’s escape by hiding in an oak tree. The date is actually the day when he was restored to the throne and his birthday. As well as decorating their doors people wore oak leaves in their lapels and their hats and to not do so could get you accused of being a Roundhead! Because it was so widely celebrated many villages had more of a party on the 29th than the 1st of May. He also mentions wassailing – he loves the idea of singing to the trees, though it is obviously too late for him to witness it (wassailing normally takes place around 17th January).

Whilst the beginning of the essay is deep inside the heart of a coombe, once he is in the Quantocks the human as well as natural observances come to the fore. He visits villages, commenting on stone crosses, such as the one at Bicknoller near to the church with a yew tree growing out of the tower as if planted by a thrush. (We know this to be Bicknoller though he does not name the village).

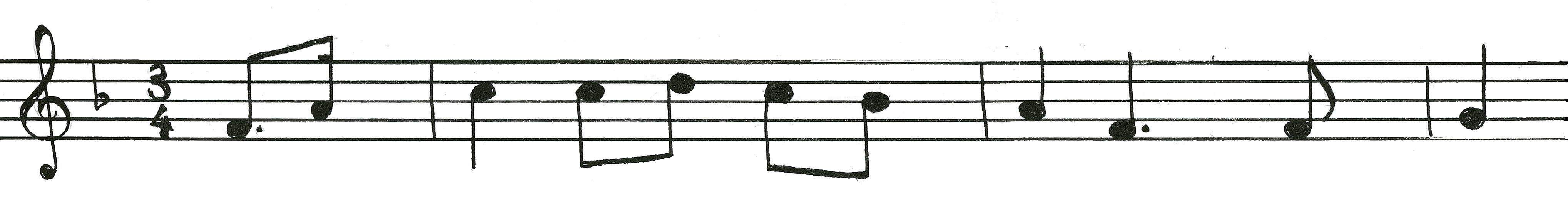

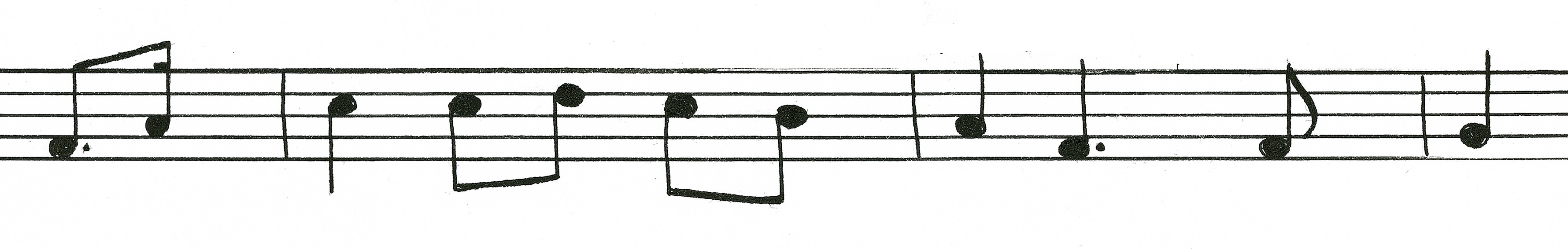

He then talks of a place nearby where another Somerset School artist Frederick Walker painted (John North of this school of painters provided beautiful drawings for the essay). We know this place to be near Halsway Manor. Yet for all these details it is still nature that reigns. The church is noted for its tree. The stone cross in the village is surrounded by wallflowers, evening primrose and stocks. Wild strawberries grow everywhere. The verdent hedgerows again alive as if creatures. Real creatures – the birds and notably otters – abound. We gain a glimpse into a landscape we can both recognise, but poignantly see is somewhat diminished in terms of biodiversity.

He then talks of a place nearby where another Somerset School artist Frederick Walker painted (John North of this school of painters provided beautiful drawings for the essay). We know this place to be near Halsway Manor. Yet for all these details it is still nature that reigns. The church is noted for its tree. The stone cross in the village is surrounded by wallflowers, evening primrose and stocks. Wild strawberries grow everywhere. The verdent hedgerows again alive as if creatures. Real creatures – the birds and notably otters – abound. We gain a glimpse into a landscape we can both recognise, but poignantly see is somewhat diminished in terms of biodiversity.

The essay ends drifting west again, at Selworthy with its thatched manor and descriptions of birds. A gentle end to an essay in atmosphere; an essay that captures the heart of the Quantocks.

Jefferies himself is an interesting man as a writer, widely regarded now as one of the greatest nature writers at a time when nature writing has had a resurgence and its history is rightly gaining more notice. Born in 1848, Jefferies was a native of Wiltshire and published many books (including fiction) and essays in his lifetime, but one of the reasons he is most interesting and quite revolutionary is his approach to place. He captures the minute detail that naturalists at the time were fixated with, that great Victorian pre-occupation with cataloguing and catagorizing (this is the age of the encyclopedia after all), but he also writes about the feelings of place and in some of his more experimental and philosophical work what that might mean.

He talks of atmosphere as a living thing and that to breathe it is life itself. He talks of the idea of soul-thought – a way of experiencing and being that has the intensity of a religious experience, but is of the human in connection with the earth and its feelings and memories. This can still sound eccentric today, and in the mystic tradition, but we would recognise his way of being of feeling of trying to obtain a deeper connection with nature and the earth.

He left a legacy of intense minute description, making us notice what is there right in front of us for all to see, and a legacy of atmosphere and descriptive feeling, helping us get to know the places he visited in a different way, the layers of them, the complex beauty and feeling of places, as if individuals, not swathes of land to be simply noted down. His “Summer in Somerset” is no different – of all the writing on the Quantocks this short piece conjures the hills like no other, making the 19th century drift into our 21st century minds and showing us their intrinsic spirit is not that different; it is very much there.